Francis Fox Piven made a striking statement in her book, Challenging Authority: How Ordinary People Change America. “Almost all of the labor, civil rights, and social welfare legislation of consequence in the industrial era,” she wrote, “was enacted in just two six-year periods: 1933-1938 and 1963-1968.”

The sole exception is SSI, but even that program was worked out during the 1963-1968 “big bang,” although its actual enactment was delayed for technical reasons. All the rest – Social Security, the first federal minimum wage, laws legitimizing the labor movement, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and another civil rights act in 1968, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Medicare and Medicaid, anti-poverty programs such as Head Start, and abundantly more – came in the big bangs.

History, at least in the U.S., seems to have affirmed Lenin’s statement that “there are decades where nothing happens and there are weeks where decades happen.” How can this pattern be explained?

Both big bangs coincided with periods of extraordinarily high levels of grassroots activism. If you were alive in the 1960s, you experienced a volume of activism greater by orders of magnitude than anything since in the United States: protests, marches, sit-ins by blacks at whites-only lunch counters, school strikes, and all sorts of disruptive actions coming from everywhere, all the time. The actions were often met with violence from the authorities. You saw the photographs.

Both big bangs coincided with periods of extraordinarily high levels of grassroots activism. If you were alive in the 1960s, you experienced a volume of activism greater by orders of magnitude than anything since in the United States: protests, marches, sit-ins by blacks at whites-only lunch counters, school strikes, and all sorts of disruptive actions coming from everywhere, all the time. The actions were often met with violence from the authorities. You saw the photographs.

It wasn’t pretty, but at the same time you read reports of more and more black people getting registered to vote, even in areas where violence was routinely used to prevent voting by blacks. You heard of lunch counters, churches, skating rinks, and facilities of all sorts welcoming black customers for the first time.

The big bang in the 1930s also had oceans of people bearing signs, along with its own peculiar style of defiance, which elicited violence from the authorities. But union organizations like the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) experienced a golden age in the 1930s, with frequent successful strikes, big organizing drives, growing memberships, and high public approval.

Piven plausibly explains not only the stasis during non-bang years, but why a certain kind of activism causes laws to change while other kinds of activism fail to do so. In brief, your job as an activist is not merely to get the right people elected, nor to win the hearts and minds of the people and their political leaders, as many seem to believe today, but to make politicians fear that if they don’t fix what needs to be fixed their support will walk away.

You can receive a copy of Piven’s book if you come to my table at FreedomFest July 21-24 in Rapid City, South Dakota, where I will be distributing copies thanks to the generosity of an anonymous donor.

Piven’s causal mechanism is just one of two areas of knowledge that today’s rebels must master if they hope to create a big bang. The other is how to make a mass uprising happen.

My research rediscovered a little-known group called the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “Snick,”) about which I had only vague memories. I learned that SNCC was by far the most influential force in the civil rights movement. They were at least major actors, but usually the creators, of almost all the major events of the movement. How did they do it?

SNCC left behind a large body of documentation that was conscientiously collected and, thanks to Google and the internet, can be accessed and studied. If you spend enough time reading these materials, you will gain a clear insight into the minds and souls of the SNCC members and the rebels they worked with. They told us in the plain language of ordinary people what they did, why, and how.

left behind a large body of documentation that was conscientiously collected and, thanks to Google and the internet, can be accessed and studied. If you spend enough time reading these materials, you will gain a clear insight into the minds and souls of the SNCC members and the rebels they worked with. They told us in the plain language of ordinary people what they did, why, and how.

That is how I discovered The Method. It has no name, and it is radically different from any method being used today, as far as I know, by organizations promoting freedom or liberty. It had almost vanished from history. SNCC people and their local confederates were taught The Method and used it nationwide to instigate the mass uprising that forced policy reform.

History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme. In my research I returned to the first big bang, the one in 1933-1938. That grassroots upheaval was organized mostly by communists, socialists, and the like. The CIO was the leading institutional force.

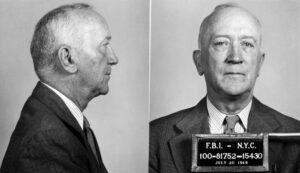

William Zebulon Foster, who later became National Chairman of the Communist Party, was considered one of the very best labor organizers. In 1936 he published his pamphlet, “Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry.” The following year he published another pamphlet, “What Means a Strike in Steel,” which discussed strategy and tactics as well as organizing methods, and was considered the “Bible” for labor organizers. It was in wide use during the 1930s, according to his biographer.

William Zebulon Foster, who later became National Chairman of the Communist Party, was considered one of the very best labor organizers. In 1936 he published his pamphlet, “Organizing Methods in the Steel Industry.” The following year he published another pamphlet, “What Means a Strike in Steel,” which discussed strategy and tactics as well as organizing methods, and was considered the “Bible” for labor organizers. It was in wide use during the 1930s, according to his biographer.

You can find both pamphlets online. Within them is Foster’s description of The Method in a cruder, labor-oriented version. It seems that SNCC adopted it and added their own upgrades.

My paper, “Organizing a Mass Uprising,” combines Piven’s theory with The Method as applied in CIO/SNCC practice and supported by modern psycho-social science. It is a field manual that will be available at my FreedomFest table.

We can make the next big bang happen. We know what to do and how to do it. With the right theoretical tools we can make a revolution in a better way, more efficiently than ever before and with a lower body count. Today we need a world-wide, permanent, pro-freedom equivalent of SNCC to rid us of the bane of excessive government. It’s time to start building.

Dale Woolridge holds a scientifically-oriented Ph.D. in social psychology. He is a veteran of the student movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and fought against the Viet Cong insurgency during the Vietnam War. He has been a government manager and conservative/libertarian political activist.